Abstract

Activity Overview

Teams of students – with guidance from technical and clinician mentors – were tasked with developing technological solutions to challenges faced by Singapore in its fight against COVID-19. Designed and delivered in collaboration with clinicians from a local hospital, the activity gave students a unique immersion in a real-life public health challenge.

Independent review

The success of the activity was underpinned by the long-standing collaboration between SUTD and a local hospital as well as by the technical and clinical mentorship offered to teams. As an online activity, it enabled synchronous engagement of clinical mentors in a way that would not have been possible face-to-face.

Activity details

A two-day extracurricular challenge, newly established for 2020, that was open to any current or incoming SUTD undergraduate. Delivery was 100% online and 100% synchronous. Teams developed their solutions using story-boarding and/or 3D modelling; no physical prototyping was involved.

Activity overview

The Virtual Ideation Challenge (VIC) was a two-day extracurricular activity where current and incoming SUTD undergraduates connected with clinicians from a local hospital to tackle key technological challenges under the theme of “reimagining healthcare in the time of COVID-19”.

Held over a weekend in June 2020, the VIC was a 100% online activity delivered as a partnership between SUTD and a team of clinicians from the COVID-19 response team at Changi General Hospital (CGH), an academic medical institution serving a community of more than one million people in eastern Singapore. Participating students – from across all SUTD disciplines and academic years – were divided into teams, with each tackling one of 14 ‘case scenarios’ devised by the CGH clinicians. The scenarios described 14 challenges faced across the three major phases of the clinical and public health response to COVID-19 in Singapore: pre-pandemic (preparations for a pandemic); ongoing pandemic response (pandemic response); and post-pandemic (the ‘new normal’).

The opening session on the first day introduced students to the context for the VIC. It included webinars from CGH clinicians, as well as videos and a 360⁰ interactive tour of the CGH Emergency Medicine department, CGH wards and migrant workers’ dormitories, the latter of which saw the rapid spread of COVID-19 in the early weeks of the pandemic. From there, the VIC took a highly structured approach to guide students step-by-step through a design and ideation process over the two days. Online support, mentorship and facilitation for the student teams was provided by a group of graduate mentors and CGH clinician mentors. At the close of the two days, teams presented their design-thinking process and proposed the solution to their assigned challenge arising from COVID-19 to a judging panel via a five-minute online pitch.

Independent review

Distinctive feature

Although the VIC incorporated a number of innovative features – such as the inclusion of incoming (yet to matriculate) as well as current SUTD undergraduates – one feature sets the activity apart overall: the active engagement and collaboration with external partners. The VIC was designed and delivered in close partnership with clinicians at a local hospital (CGH). Interviewee feedback made clear that the unique immersion offered to students in a real-life public health challenge, with dedicated support from clinician mentors, would not have been possible if the experience had been delivered face to face.

Success factors

Feedback and reflections from interviewees pointed to four factors that were crucial to the success of the VIC, as listed below.

The first factor was the ‘virtual immersion’ in the challenge context. Student participants were offered unique access to the national COVID-19 environment, from both clinical and public health perspectives, with exposure to the ‘front line’ of Singapore’s response in a local hospital and migrant workers’ dormitories. This immersion in real-world contexts, together with the targeted support offered by clinical mentors, was pivotal to the students’ progression in this time-limited activity and supported the development of insightful and innovative solutions. Interview feedback made clear that this access to and mentorship from clinicians also underpinned high levels of student engagement and focus, despite many working with previously unknown team-mates in an online environment.

The second factor was the on-demand, flexible support offered. Participants spent the majority of the two-day challenge working in Zoom break-out rooms with their team. Given that more than half of participants had yet to start their formal studies at SUTD, a lack of clarity on both the design process and the VIC deliverables presented a real risk for teams in this time-limited activity. However, interview feedback suggested that the on-demand facilitation offered by the graduate mentors allowed teams to call for support as and when needed. Facilitators offered practical support and helped students develop the types of mindset and approach that might help them to tackle the challenge.

The third factor was the close working relationship between SUTD and CGH. The VIC built on an established working relationship between SUTD and CGH, which had already seen the development of a new undergraduate healthcare educational partnership. The trust built through this relationship, as well as a pre-existing understanding of constraints and opportunities offered by each partner, appears to have been pivotal to the rapid implementation of this activity and its ability to enrol so many clinical mentors.

The fourth factor was the levels of pre-planning put in place. The VIC was devised and designed in a very short time period; in the three weeks prior to its launch. Despite this rapid turnaround, considerable time and staff resources were invested in planning and preparation for the activity. For example, in addition to training of the graduate mentors, rehearsals were held with clinician mentors and activity judges to identify and resolve any technical issues and ensure that all contributors understood the challenge context, the scoring rubrics, and the structure of the two days. The organisers also prepared back-up versions of all presentations in case of network problems, and located organising committee members in different parts of Singapore to minimise the impact of any internet connectivity issues arising in particular geographical areas.

Challenges faced

Interviewee feedback pointed to two key challenges faced in the delivery of the activity. Strategies are in place to tackle these issues in any future deliveries of the activity. These changes are outlined below.

The first challenge was the lack of breaks in the two-day schedule. Although the activity scheduled two half-hour breaks for lunch each day, in reality, team-working and mentoring sessions expanded to fill the whole two days. With no formal schedule for mentors or event organisers to check in on teams, students were often left unsure when they were able to take breaks from their screens. As a result, most teams continued to be logged on throughout both days, without taking formal breaks, leaving many fatigued by the close of the activity. For future iterations of the activity, organisers plan to embed mechanisms by which teams are able to take structured breaks from working without penalty to their access to mentoring support.

The second challenge was the omission of hands-on, prototyping opportunities. Hands-on learning and prototyping are core features of the SUTD education, features which are highly valued by current and prospective students alike. It is therefore perhaps not surprising that participants pointed to the lack of a prototyping element as a weakness of the VIC. While embedding a hands-on element was not feasible for the 2020 activity, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, plans are in place to support prototype development for future iterations of the activity.

Advantages of online delivery

Interviewee feedback suggested that the online format of the VIC offered important advantages to the organisation of the activity and to student learning, beyond what might have been possible if the activity took place face to face.

The key benefit was the ability to secure a group of 21 clinicians – each of whom was involved in the screening, prevention and treatment of COVID-19 in Singapore – to play an active role in this synchronous activity, through offering information, support and mentorship to the student participants. As many interviewees noted, it would not have been possible to secure the time of this group if they had been required to travel to the SUTD campus to make these contributions. With clinicians dialling in remotely from home, work or while commuting, the online nature of the activity facilitated such real-time connection.

Interviewees also pointed to a number of other benefits of the activity’s online delivery. For example, the ways in which teams were able to connect with design mentors – through the messaging app Telegram – allowed them to benefit from targeted support as and when needed, with mentors able to join the team almost immediately upon a request for help. Some also noted that the online nature of the activity supported ongoing sharing of learning between teams, with students benefitting from accessing the questions posed by peer teams through the messaging app and learning from the responses given by mentors and organisers.

Activity details

Participants and project groups

Around half of the 58 participants were ‘future’ SUTD students, due to start their undergraduate studies in September 2020. Students were given the option to form their own teams. The remaining participants were allocated to teams based on a pre-activity survey of students’ prior experience with the design process and their personality profile. It was a requirement that all teams contained at least one current student (who had therefore participated in SUTD’s Introduction to Design course and had prior experience of undertaking design projects).

Structure of the two days

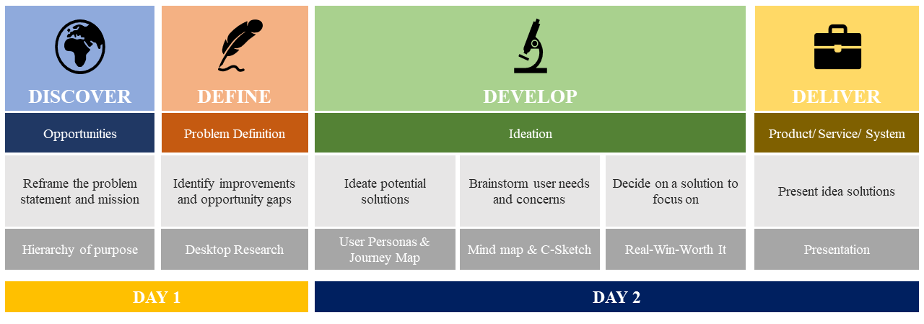

Structured around the ‘4D’ (or ‘Double Diamond‘) design process, the two-day activity is divided across the four stages of Discover, Define, Develop and Deliver:

| 1.Discover | The opening session, on the Saturday morning, exposed students to the environment and challenges at the front line of Singapore’s response to COVID-19, to set the stage for the VIC. Activities included: a panel from CGH to provide perspectives from the hospital and public health sector; videos highlighting particular challenges in the management of hospital wards and screening processes; an interactive virtual tour of the wards and migrant workers’ dormitories. Students were also given a 40-minute ‘crash course’ in design methods and the ideation process, which was particularly targeted at the ‘future’ SUTD students who had not yet experienced the SUTD approach to design. At the end of this opening session, students were introduced to the 14 different ‘case scenarios’, each identifying a key challenge facing Singapore’s pandemic response. Teams selected their preferred challenge (allocated on a first-come-first-served basis) and opened discussions on their problem statement and mission. |

| 2.Define | During the second session, on the Saturday afternoon students reframed their problem statement for their challenge, identified existing solutions and defined their team mission. On-demand facilitation and guidance was provided by graduate mentors. In addition, clinical mentors connected with teams to provide background information and answer any questions they had about their challenge context. |

| 3.Develop | In the third session, on the Sunday morning, teams used user personas and journey maps to explore the challenge from the end-user perspective, and developed a range of possible solutions. Teams undertook a ‘mindmapping’ process – based on user needs and concerns – to explore the feasibility, practicality and usability of each solution. Collaborative sketching and/or 3D modelling were also used to illustrate their ideas. Teams then selected and developed their preferred solution, which were further refined in discussion with their clinical mentors before their presentations. |

| 4.Deliver | In the final session, on the Sunday afternoon, teams developed and delivered a five-minute pitch of their challenge, design process and idea. The pitch was delivered to a panel of judges which included the then Chairman of the Medical Board of CGH, SUTD leadership, and the director of the SUTD Entrepreneurship Centre. As each team tackled a different case scenario, the final session exposed participating students to 14 different challenges and solutions across all three pandemic phases: pre-pandemic; ongoing pandemic; and post-pandemic. Similar to the opening ‘Discover’ session, these presentations were open to the wider SUTD and CGH communities. |

The challenge brief

Teams were asked to select one ‘case scenario’ and associated problem statement from 14 options presented by CGH clinicians around the theme: “Re-imagining healthcare in the time of COVID-19“. Case scenarios were allocated to teams on a first-come first-served basis, such that each challenge was being tackled by one team. The 14 case scenarios posed by the clinicians spanned the three key stages of a disaster response cycle:

| Pre-pandemic | Five ‘case scenarios’ were set in the pre-pandemic stage, which focused on mitigation and preparedness. One sample case scenario and problem statement are given below: Case scenario: International surveillance of emerging infectious diseases is an important component of the public health function. There is growing evidence that a new virus is showing regional spread in one part of the globe. The impact on Singapore needs further clarity. Problem statement: How might we use technology to monitor and assess the significance of potential infectious disease outbreaks in other countries? |

| Ongoing pandemic | Five ‘case scenarios’ were set in the current pandemic stage, which focused on the response. One sample case scenario and problem statement are given below: Case scenario: Many patients have presented to public hospitals with fever, coughing and acute respiratory distress. Their chest X-rays and CT scans show lung changes typical of COVID pneumonia. Within a few days, ICUs are caring for patients who are deteriorating and require endotracheal intubation for mechanical ventilation. The surge in demand for ventilators may pose challenges to patient care. Problem statement: How might we design a triaging tool to select which patients to intubate and ventilate, and which not to? How might we convince clinicians that the tool can make better ‘life and death’ decisions than them? |

| Post-pandemic | Four ‘case scenarios’ were set in the post-pandemic stage, which focused on the recovery and the ‘new normal’. One sample case scenario and problem statement are given below: Case scenario: The development of vaccines seems to be a constant catch-up game where respiratory viruses e.g. influenza virus, coronavirus, are concerned. This is mostly due to the rapid mutation rate of such viruses. Problem statement: How might we pre-emptively design a ‘perfect’ vaccine even before a disease outbreak begins, while ensuring that the vaccine is affordable by most countries? (After all, until all of us are safe, none of us are safe). |

Deliverables

The final deliverable – presented by student teams at the close of the two days – was a five-minute online pitch which outlined the team’s case scenario, their design process, their idea/solution, and the team’s future plans. Four judging criteria were adopted for these presentations:

- Solution fit: does the proposed solution address the problem and user needs effectively?

- Innovation: does the solution present a creative and original approach to solving the problem, that is also feasible and implementable?

- Design-thinking: how well has the team used the design-thinking framework (discover, define, develop, deliver) to inform their solution?

- Presentation: how well is the team able to articulate their proposal and engage the audience?

In addition, teams were asked to submit online a short report, which brought together the five interim deliverables that teams submitted over the course of the two days:

- refined problem statement;

- team mission;

- existing solutions to the problem statement;

- user personas;

- user journey map.

The VIC was extra-curricular and non-credit-bearing for the students’ undergraduate studies.

Learning outcomes

The four primary learning outcomes for the VIC, as specified by SUTD, are provided below:

- to engage frontline CGH clinician leaders to share their experience and perspectives on the COVID-19 crisis and its associated healthcare challenges;

- to promote SUTD’s culture of design and co-creation to current and future students;

- to introduce student participants to useful design methodology and tools;

- to provide an opportunity for collaborative team-based learning and networking.

The teaching team

The team engaged in the development and delivery of the VIC included:

- two faculty leads from SUTD and two clinical leads from CGH;

- 21 clinical mentors from the COVID-19 response team at CGH;

- five graduate mentors from SUTD, including one coordinator;

- webinar speakers, judging panel, and organising committee, including leaders, innovators and clinicians from both SUTD and CGH.

Graduate mentors had all participated in SUTD’s Innovation By Design courses, and had all attended a training session prior to the VIC. The two major areas of focus for the graduate mentors when engaging with the teams were:

- students’ mindset: ensuring that teams understand what is expected of them throughout the VIC, and (in particular) that they are punctual and play an active and positive role in their team’s activities;

- team progress: ensuring that teams are clear about the goals and deliverables for the VIC and keep on track throughout the two days.

Graduate mentors were provided with a written briefing – the ‘Facilitator’s Toolbox’ – which outlined the key priorities for facilitation, the detailed schedule for the two days, and the key team deliverables.

Technology used

The following applications and technologies were used in the delivery of the four key phases of the VIC:

| 1.Discover | Zoom was used for the webinar sessions, with student participants hidden from view except during the Q&A sessions, where they were able to ask questions using the ‘chat’ function. 360⁰ immersive cameras were used to allow students to explore the environment at the CGH emergency room and at migrant workers’ dormitories. |

| 2.Define & 3.Develop | Zoom breakout rooms were provided for each student team. All students were invited to join a private channel of the messaging platform Telegram, which allowed teams to ask questions or seek help from mentors or activity organisers in real time. Telegram was also used to broadcast instant messaging reminders to the teams about various project deadlines. Google Drive Folders contained a design toolkit for student teams, with information on the activity schedule, deadlines and templates for each of the VIC deliverables. |

| 4.Deliver | Zoom webinars were used for the closing presentations given by each team. Google Drive Folders were used for the submission of final reports from each team. |

Source of evidence

The case study for SUTD (including Part A, this review of the VIC, and Part B, the review of the ‘institutional context’) drew upon one-to-one interviews with 10 individuals: the SUTD Associate Provost; the SUTD Director of Undergraduate Studies; the two co-faculty leads of the Virtual Ideation Challenge from SUTD; two clinician mentors from Changi General Hospital (one of whom was the activity coordinator from Changi General Hospital); the coordinator of the graduate mentors for the VIC; and three SUTD undergraduates.

Further information about the methodology for development of CEEDA case studies is given on the CEEDA website About page.